Kurds, especially in Turkey, have faced some of the most systematic assimilationist policies in the Middle East since the early years of the foundation of the Republic of Turkey. The Kurds have not been allowed to establish their own centers for the production of knowledge under the uncertain and perilous conditions in Northern Kurdistan and Turkey. Therefore, the Kurds and their friends have created some indispensable organizations and platforms in diaspora to preserve Kurdish written materials and cultural artifacts from attempted state annihilation.

Finding and accessing Kurdish written materials, cultural artifacts, and musical heritage can be a major obstacle for those who are interested in Kurdish history and culture because of the policies and attitudes in the states in which Kurds live, as well as due to materials being misclassified in research libraries. For example, one of the main websites for locating manuscripts in Turkey is the General Directorate of Libraries of Ministry of Culture. When you search this website for “Kürdi,” “Terkibü’l Kürdi” (The Structure of Kurdish) is among the search results. The title indicates that it has something to do with the Kurdish language or Kurds. On the details page for this manuscript, the subject is described as “Afro-Asyatik diller Sami dilleri” (Afro-Asyatic language Semitic languages), the language section is empty, and there is no mention of Kurdish or Kurds. The second bizarre classification can be seen for “Müntehâbât-ı eş’âr-ı Kürdiyye” (Selected Poems in Kurdish), the subject is “Fars Dili ve Edebiyatı” (Persian language and literature) and again the language section is empty. These types of misclassification and absence of a language are examples of the denial of existence of the Kurdish language and Kurds. Moreover, this kind of treatment of Kurdish sources makes it more difficult for researchers to complete their work. You can support the existence of the Kurdish language, sources, and history. One of my pleas to my colleagues is this: PLEASE do not only mention the struggle of Selahadînê Eyûbî, or Saladin the Kurd, against the Crusaders during your survey classes. The Kurds have contributed more than that to the history of the Middle East. Your efforts of introducing the contribution of Kurds in different fields can challenge the policies of erosion and denial toward Kurds in the Middle East.

Therefore, in this short piece, I aim to introduce some online primary and secondary Kurdish resources and collections that might make knowledge and sources more accessible in this time of global pandemic. I will also introduce three books that are interesting examples of how Kurds have played a significant role in the history of the Middle East, the production and circulation of knowledge, the history of food, and the role of women in the history of the region.[1]

One of the most useful and convenient hubs for students and scholars to find people who are interested in Kurdish studies and Kurdistan from different parts of the world is the Kurdish Studies Network (KSN). The KSN was established in 2009, with an aim “to revitalize and reorient the research, scholarship and debates in the field of Kurdish studies and provide valuable resources by sharing knowledge and encouraging interaction and collaboration through its vast online network.” An important resource created by KSN is their bibliography of English language materials on Kurds and Kurdistan, which is divided into three subdivisions: 1) Books, from 1829 to 2019; 2) Articles, from 1838 to 2018; and 3) Chapters, from 1983 to 2015. KSN also hosts an email listserv that can be subscribed to, in order to follow and hear about scholars of Kurdish and Middle Eastern Studies. Additionally, KSN publishes an interdisciplinary, peer-reviewed publication, Kurdish Studies Journal, to which individuals or institutions can subscribe.

The Kurdish Institute of Paris, has hosted innumerable events and individuals since 1983. According to their website, the Institute’s library has the largest Kurdish collection in the Western World, including 10,000 monographs about the Kurds in 25 languages and other printed materials and music recordings. Many rare books, periodicals, and other materials, as well as some newer titles, in different languages, have been digitized and can be downloaded in pdf format via bibliotheque kurde.

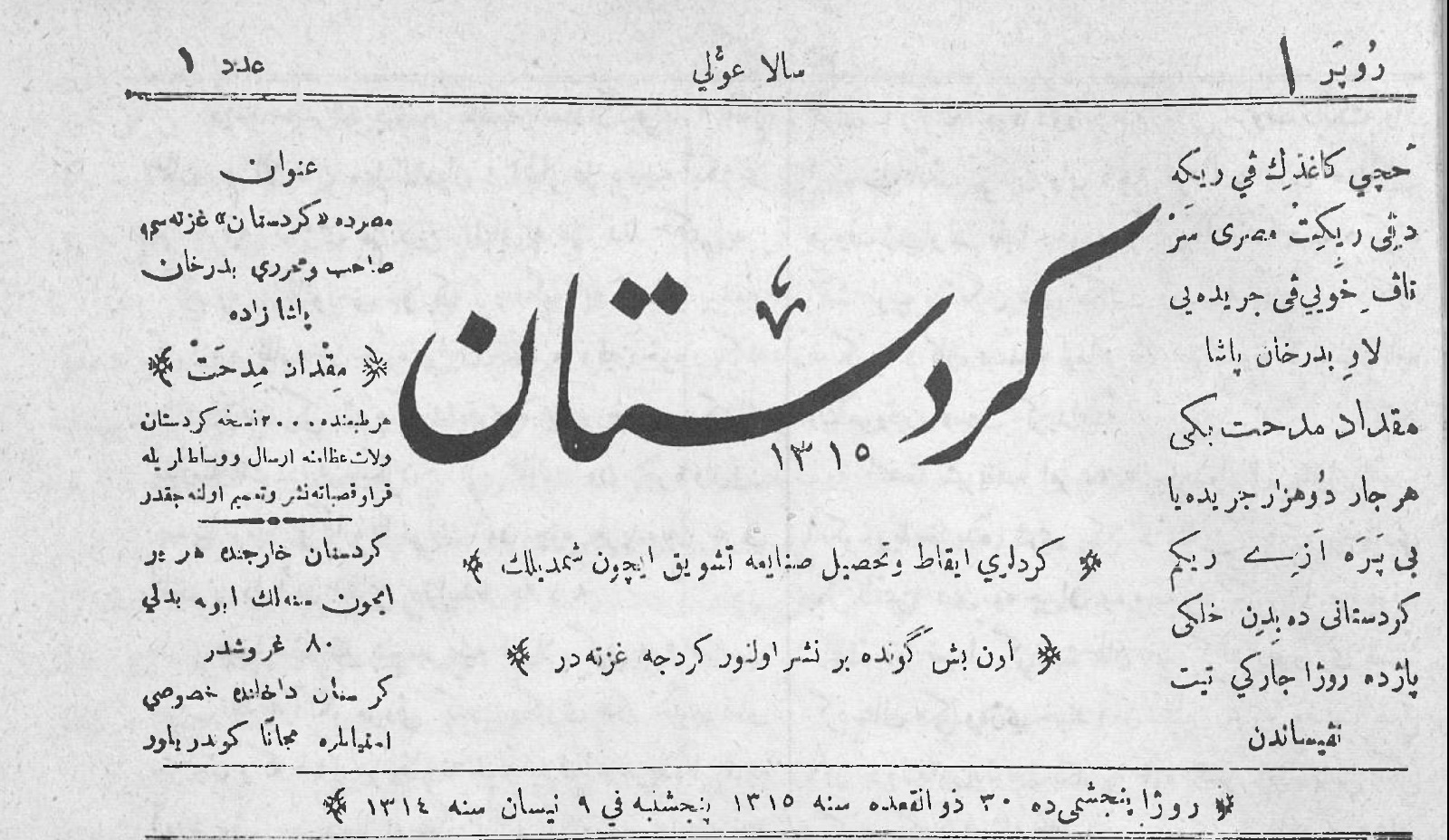

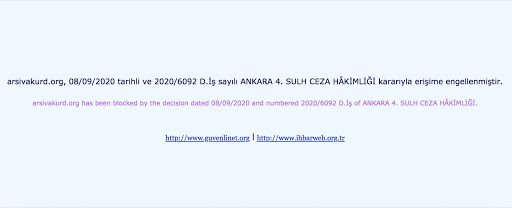

The Kurds have published periodicals in their own mother tongue, as well as other languages, since the fourth quarter of the nineteenth century. The first Kurdish newspaper, Kurdistan, was published by Mîqdat Mithad Bedirkhan in Cairo, from 1898. If you live outside of Turkey, you are able to access and download pdf copies of Kurdistan and many other Kurdish periodicals (newspapers and magazines), books, and documents related to the Kurdish history and language and Kurdish political parties and organizations via Arşîva Kurd, a website devoted to providing access to these print materials. After corresponding with the organization, I learned that a group of intellectuals, politicians, and individuals are behind the website. In terms of materials, they digitize materials as needed and sometimes bring together online materials to add to their website. Unfortunately, if you attempt to access Arşîva Kurd in Turkey you will encounter the upsetting warning seen below, which states that the website was blocked by the court. This sort of legal action is not unique in Turkey. For example, Enstîtuya Kurdî ya Stenbolê (The Kurdish Institute of Istanbul), an educational organization which focuses on the Kurdish language, culture, and history, has been shut down many times since its foundation 1992 by the Turkish State.

SARA Distribution was established in 1987 in Stockholm, Sweden. The founder and owner of SARA Distribution (The Kurdish Museum), Goran Candan, has collected rare books, periodicals, artifacts, and music related to Kurds, in Kurdish and many other European and Middle Eastern languages. The Kurdish Exile Museum is a website on which you can find these incredible materials and documents. In particular, their stamp collection, postal cards, and Kurdish music are worth a look. You can see these items through browsing.

Friends of Kurds and Kurdish language lovers have been instrumental in bolstering and preserving Kurdish resources and arguing for the necessity of basic human rights for Kurds. Scholar and archivist of Kurdish culture, Vera Beaudin Saeedpour (1930-2010), was one such individual who started the Kurdish Heritage Foundation, Kurdish Library, and Kurdish Museum in Brooklyn, New York, in the early 1980s. She also published two important Kurdish journals: The International Journal of Kurdish Studies and Kurdish Life. Vera Saeedpour’s invaluable treasure trove of materials and artifacts can now be found at the Binghamton University Libraries. The Vera Saeedpour Kurdish Library and Collection consists of 3,000 books, journals, and newspapers in Kurdish and many other languages. More details about the written materials in their collection can be found via their finding aid. In addition, the collection contains some jewelry, headpieces, belts, musical instruments, and recorded music, as well as textiles, of which images can be viewed on their website, along with descriptions. If you have a chance to visit upstate New York (fall, in particular, is recommended), please visit the Kurdish collection display at Bartle Library at Binghamton University (SUNY).

Recently, information about the documents and collections of two eminent Kurdish figures, Professor Amir Hassanpour (1943-2017) and Professor Omar Sheikhmous (1942-), have been made available to the public. Hassanpour was Professor Emeritus of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations at the University of Toronto. The Amir Hassanpour Fonds containshis correspondence with other Kurdish figures, his works, interviews, publications, and more materials.The finding aid describing the fonds is available in Kurmanji, Sorani, Persian and English. Sheikhmous, an influential scholar, activist and translator, has donated his books, personal papers, and periodicals to the University of Exeter, where the Centre for Kurdish Studies has held numerous important events and conferences. Archivist James Downs has written a series of four blog posts in which he highlights Sheikhmous’ contributions and the content of the materials. The third blog post, “Kurdish Studies and the Archive”‘ highlights some important points and raises some important questions for the development of Kurdish Studies as a discipline.

Librarian and curator, Michael James Erdman has written about and explored Kurdish historical sources at the British Library. Particularly, his blog post “A Testament to Diversity: Kurdish Manuscript Collections at the British Library” is worth reading. In addition to that, he has prepared two important lists related to Kurdish periodicals at the British Library.

In addition to these online resources, I would like to briefly introduce three interesting books that were widely distributed in Northern Kurdistan and Turkey. The first account is a partially Kurdish translation of a famous Greco-Roman physician and philosopher, Gelanos (129-216 CE) (also known as Galen or Calînûs Hekîm), by Kurdish scholar Melayê Erwasî (18th-19th c.).[2] Melayê Erwasî not only benefitted from Gelanos’ book, he also included some names of items that did not exist in Gelanos’ time, such as tobacco.[3] Written in the 18th century, Tiba Melayê Erwasî (The Medical Book of Melayê Erwasî), was written in very simple Kurdish, which makes the book an easy read. He begins the book with “Calînûsê Hekîm gotiye” (“Physician Calînûs had stated”) and he supplies details about many diseases and what a person should do they are experiencing symptoms.

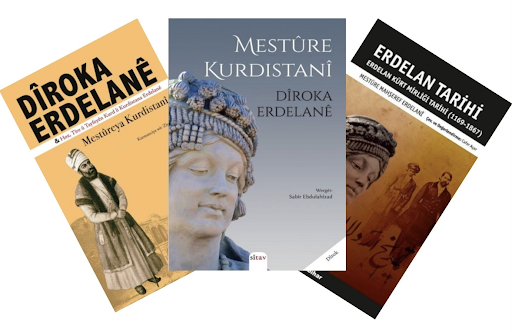

Second, a book by Mestûrê Mahşeref Erdelanî, or Mestûreya Kurdistanê (1805-1847/8), Tarikh-i Ardalan (The History of Ardalan) was written in the mid-nineteenth century. This book has been translated into Kurdish and Turkish recently in Turkey and Northern Kurdistan.[4] Mestûrê Xanim covers the history of the Kurdish Ardalan Dynasty, their relationships with local and imperial powers, and some details about her own life. Unfortunately, we do not have many books that were written by female historians from this time period in the Middle East. This makes Mestûrê Xanim a notable individual who produced books not only on history, but also on religious matters as well.[5]

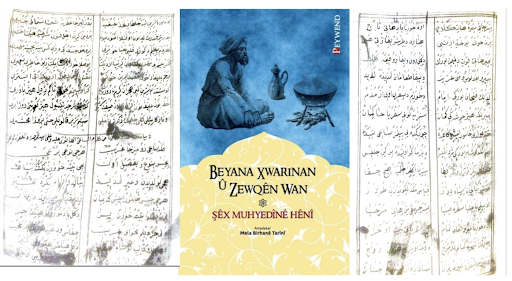

Finally, Şêx Muhyedînê Hênî’s (1849-1897) Fi Beyanî’l Et’îme we Mezaqîha, or, in Kurdish, Beyana Xwarinan û Zewqên Wan (Recipes for Foods and Descriptions of Their Taste).[6] This cookbook is unique in its subject matter and is the oldest cookbook in the Kurdish language, from the nineteenth century. This noteworthy book was edited and transliterated by Mela Birhanê Tarînî in 2015. Şêx Muhyedînê Hênî describes many foods from different cities of Kurdistan and emphasizes what food should be eaten under which circumstances in 186 couplets. Additionally, the book illuminates an interesting picture of the various social classes, through Şêx Muhyedînê Hênî’s explanations of which classes ate which foods and eating habits in Ottoman Kurdistan. Interestingly, he also describes the foods that the Prophet ate and liked. Beyana Xwarinan û Zewqên Wan mentions 130 different foods and broadens our understanding of the foods and flavors of the Middle East from a Kurdish Sufi Naqshbandi/Khalidi perspective.

Hopefully, we will see these three important Kurdish books, and others, translated into English, so that scholars from around the world will be able to benefit from them.

Bahadin H. Kerborani is a PhD student focusing on the history of the Ottoman Empire, Yezidis, and Kurds in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He examines the agency of local ethnic and religious groups and their responses to the reforms and developments of the era in Ottoman Kurdistan. He is also interested in the use of Kurdish written sources in the history of the MENA region.

This article was initially published on Hazine: https://hazine.info/author/bahadin-h-kerborani/

[1] Some historical sources can be found at: Kurdish Sources and the Khalidi Library.

[2] We do not know the exact date of the book; some scholars claim that it could be from the seventeenth century.

[3] Kadri Yıldırım, Ji Sedsala 18. Pirtûkeke Kurdî ya Bijîşkiya Gelêrî: Tiba Melayê Erwasî (Istanbul: Berdan, 2013). 20.

[4] Mestûreya Kurdistanî, Dîroka Erdelanê: Hoz, Tîre û Tayfeyên Kurd li Kurdistana Erdelanê trans. by Ziya Avci (Istanbul: Avesta, 2020), Mestûre Mahşeref Erdelanî, Erdelan Tarihi: Erdelan Kürt Mirliği Tarihi (1169-1867) trans. by Cafer Açar (Istanbul: Nûbihar, 2020), and Mestûre Kurdistanî, Dîroka Erdelanê trans. by Sabîr Ebdulahîzad (Van: Sîtav).

[5] Mah Sharaf Khanum Kurdistani, ‘Aqayid, (Stukhulm: Pencînar, 1998), this book was translated into Turkish by Hatice Yılmaz Aslan as Şer’iyat Risalesi: Bir Kürt Alimenin Fıkıh Kitabı (Istanbul: Nûbihar, 2014).

[6] Şêx Muhyedînê Hênî, Fi Beyanî’l Et’îme we Mezaqîha (Beyana Xwarinan û Zewqên Wan) edited and transliterated by Mela Muhyedînê Tarînî (Istanbul: Peywend, 2015). Şêx Muhyedînê Hênî’s tombstone was found recently.